A Set of Pi for Ellipses

| 7 mins | Bobtags: mathematics, engineering, visualisation

On last Pi-Day, I’ve sent some friends a poster showing an approximation of \(\pi\) that is individual to them. You can find an example of “my” \(\pi\) here. This time, however, I wanted to calculate the actual Pi as accurate as I could. By hand. Entirely.

So I decided to do it up to the 20th decimal place, fairly accurate and the involved numbers will be small enough to fit on printing paper. The method I wanted to use was invented by the great Newton in 1666:

\[\pi = 2\, \sum^{\infty}_{k=0}{\frac{2^k\, k!^2}{(2\, k + 1)!}}\]Silly me, I underestimated the amount of work I just created from nothing – by a whole lot. At the time of writing this, I spent about three weeks of completing small calculation steps each evening. I got to the 9th decimal place, which sounds as if I were almost half way through, but the involved numbers get exceedingly larger for each new digit. My guess would be that I’ve probably done a good quarter. So I am very sorry that I won’t present you my result today but hopefully I’ll find the time to show you in the next few weeks.

But don’t leave yet! I have something else for you on pi-day instead. Inspired by a recent video by Matt Parker1, I wondered what a more engineering-like way of calculating an ellipse’s perimeter could be. First, a bit of mathematical background on this is necessary.

The perimeter of a circle with radius \(r\) is rather simple:

\[C = 2\,\pi\,r\]For ellipses with axes \(a\) and \(b\), textbooks (even academic literature!) show a similarly simple equation for their perimeter – without any note on how bad of an approximation it actually is:

\[E \approx \pi\,(a + b)\]If you want to get more details on how inaccurate it is and what other approximations2 there are (Parker and also Ramanujan made good ones), check the video I mentioned above. Basically, the major problem with all approximations is that they are only acceptable for small ratios \(b / a\); in other words, the closer it is to a circle, the more accurate they are. The actual perimeter can, however, only be determined by an infinite series. Here is a neat one by James Ivory3:

\[E = \pi\,(a + b)\,\sum^{\infty}_{n=0}{h^n\,\left(\frac{(2\,n-3)!!}{2^n\,n!}\right)^2}\] \[E = \pi\,(a + b)\,\left(1 + \frac{h}{4} + \frac{h^2}{64} + \frac{h^3}{256} + \frac{h^4}{16384} + \frac{h^5}{65536} + \frac{h^6}{1048576} + \cdots\right)\]The funny denominators can also be found in A0569824. The variable \(h\) is a relation between \(a\) and \(b\):

\[h = \left(\frac{a - b}{a + b}\right)^2\]But wait, look! There’s \(\pi\) in there, which itself is always just an approximation and requires infinite series to be exact – like the one by Leibniz5 (or Newton’s one you’ve seen above):

\[\pi = 4\,\sum^{\infty}_{n=0}{\frac{(-1)^n}{2\,n + 1}}\] \[\pi = 4 - \frac43 + \frac45 - \frac47 + \frac49 - \frac4{11} + \cdots\]Thus, the circle-number \(\pi\) and the “correction-factor” by Ivory could be put together into an ellipse-number which is dependent on \(a\) and \(b\):

\[\iota(a,b) = 4\,\sum^{\infty}_{m=0}{\frac{(-1)^m}{2\,m + 1}}\,\sum^{\infty}_{n=0}{\left(\frac{a - b}{a + b}\right)^{2\,n}\,\left(\frac{(2\,n-3)!!}{2^n\,n!}\right)^2}\]Then, the perimeter of an ellipse is:

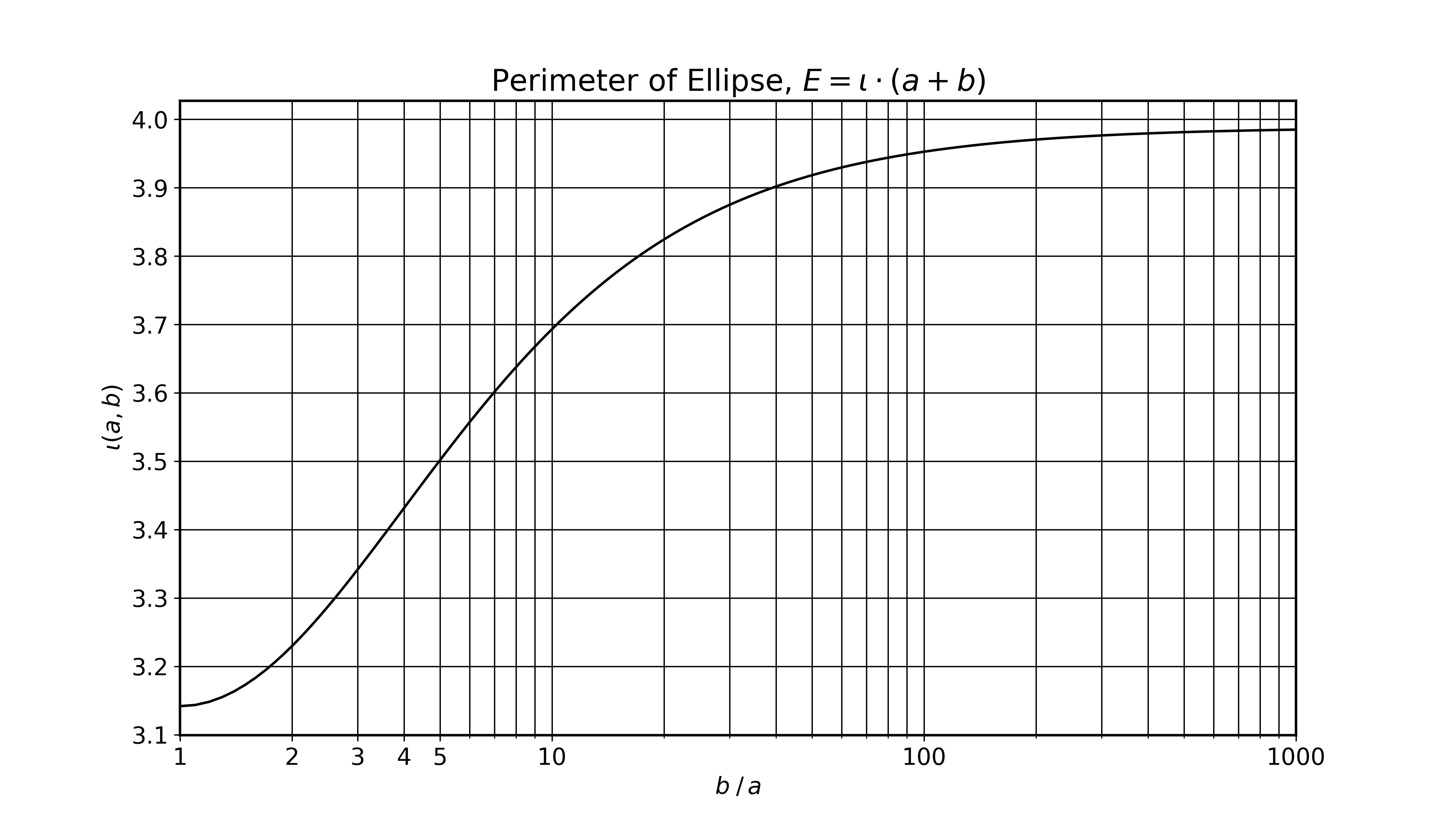

\[E = \iota\,(a + b)\]You, just as myself, probably don’t want to bother with all of this. And you also won’t need it as accurate in terms of decimal places, but you want to have at least some accuracy, no matter how stretched your ellipse is. And what do all engineers love? Diagrams of course! So here, you have one showing the ellipse-number \(\iota(a,b)\) for shapes ranging from a true circle up to ellipses 1000 times as wide as high – that should suffice.

Now, you can take any ellipse, determine the ratio of axes \(b/a\), look into this plot and find \(\iota\) to roughly two decimal places. Doing so will give you a lot more accurate results. Here is a quick comparison6:

| Ellipse with ratio \(b/a = 1.5\) | value | error |

|---|---|---|

| real \(E\) | \(7.9327\cdots\) | \(-\) |

| \(E = \pi\,(a+b)\) | \(7.8539\cdots\) | \(0.99\%\) |

| \(E = \iota\,(a+b)\), from plot: \(\iota = 3.18\) | \(7.95\) | \(0.22\%\) |

The errors of the rough approximation and the manual reading from the diagram are fairly similar and below \(1\%\), but simply using \(\iota\) with only two decimals is already more accurate than using \(\pi\) which is built into calculators with a lot more digits!

| Ellipse with ratio \(b/a = 5.7\) | value | error |

|---|---|---|

| real \(E\) | \(23.727\cdots\) | \(-\) |

| \(E = \pi\,(a+b)\) | \(21.048\cdots\) | \(11.29\%\) |

| \(E = \iota\,(a+b)\), from plot: \(\iota = 3.55\) | \(23.785\) | \(0.24\%\) |

This is where the approximation has become unacceptably bad, but look at the plot version! Still far below \(1\%\) error!

| Ellipse with ratio \(b/a = 75\) | value | error |

|---|---|---|

| real \(E\) | \(299.51\cdots\) | \(-\) |

| \(E = \pi\,(a+b)\) | \(238.76\cdots\) | \(20.28\%\) |

| \(E = \iota\,(a+b)\), from plot: \(\iota = 3.95\) | \(300.2\) | \(0.23\%\) |

You might not need ellipses this wide, but when you do, you’ll get a perimeter accuracy worse than what the Egyptians might accomplished on papyrus. Using the plot, you’ll still get the same small error as for the other ratios. Not bad right?

Also, just by the looks of it, you’ll guess \(\iota\) will eventually max out at \(4\). Thats because at \(b/a \rightarrow \infty\), the ellipse would stretch to two (almost) parallel lines of length \(2\,b\), so \(4\,b\). In relation, \(a\) is practically nothing, but the two lines would still be \(2\,a\) away from each other. You’ll have to add this gap on the left and right of the ellipse, so \(4\,a\). Combined, the perimeter becomes \(E^{\infty} = 4\,(a+b)\), which is not very useful because that ellipse would either be a straight line or infinitely large.

Thanks for reading this unusually mathematical article and I hope you’ll have a joyful pi-day, too.

-

Not recent at all, it was last year already! Watch it on YouTube. ↩

-

More in-depth mathematical and historical knowledge on approximating ellipse perimeters was put together by G. P. Michon. ↩

-

Entry in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences: A056982 ↩

-

Very inefficient series but easy to show here. More details are in this maths wiki. ↩

-

In these example calculations, \(a = 1\) and \(b = 1\,b/a\). The absolute value of the perimeter will change depending on \(a\), but the errors will stay the same. ↩